Shooting in Manual mode might seem intimidating for beginners. And there are other shooting modes that make things a little easier for shooting a great shot. But when it comes to taking the perfect shot, it’s best to take full creative control and shoot in Manual mode.

Lots of professional photographers make using Manual mode seem easy. But if you’re worried about how to get started, we’ve got all the tips you need. And if you’re shooting digital photography, you’ll never run out of film, making it cheap, fun, and easy to experiment.

Continue reading for everything you need to know about shooting in Manual mode.

How to Shoot in Manual Mode

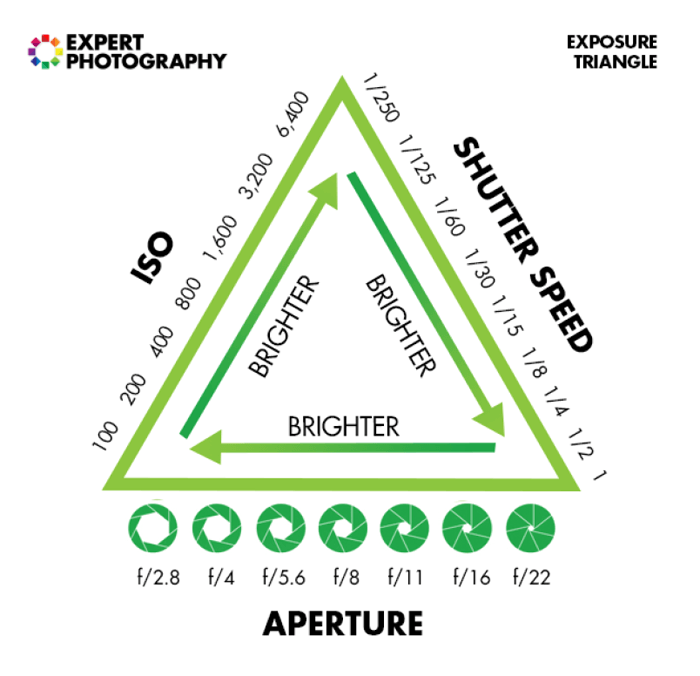

The advantage of shooting in Manual mode is that you choose every aspect of exposure. That means you have complete control over how the shot looks. There are three essential elements to exposure that make up the exposure triangle. They are ISO (or film speed/sensor sensitivity), aperture, and shutter speed.

For any given scene, there is a set amount of light that will land on your sensor. For a photo to be correctly exposed, you need to let the right amount of light through the shutter. Using Manual mode means you can adjust the three elements of exposure to make the photo happen.

We’ll explain each of these elements in this article so you can understand how to use them to your advantage.

We’ll explain each of these elements in this article so you can understand how to use them to your advantage.

- How to Set Aperture

- How to Set Shutter Speed

- How to Set ISO

- Problems and Solutions for Using Auto ISO

Manual Mode Settings

Let’s look at what it means to manually set each of these settings.

Aperture

The aperture is the hole in the lens that opens to let light fall on the sensor. Pretty much every lens has an adjustable aperture. Mirrorles lenses are an exception to this. These lenses, like the Tokina AT-X AF SD 400mm f/5.6, have a fixed aperture. But most lenses will have a way of making the aperture smaller or larger.

The size of the aperture is expressed as a number, and known as the f-stop or f-number. A lens description always includes the largest aperture possible. For example, the Tokina lens above has a maximum aperture of f/5.6.

This is the important number, because lenses with wider maximum apertures (also known as “fast” lenses) are more expensive to make. They need more glass, making it more expensive to manufacture it to a high standard.

The minimum aperture is less important and will be f/22 for most lenses. Some will go smaller, but that’s unusual.

Changing the aperture has two main effects. The larger the aperture, the more light passes through the lens barrel and onto the sensor. So you might increase use a wider aperture if the picture is too dark.

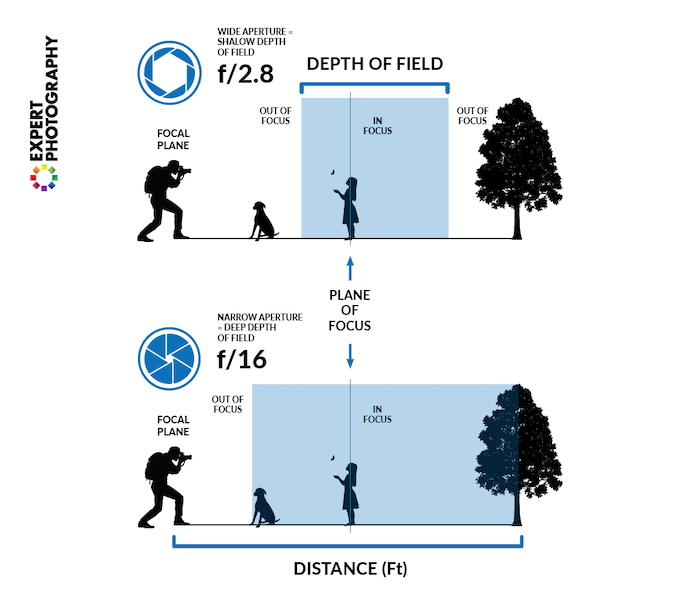

The aperture also controls the depth of field, which is how much of the scene is in focus. The wider the aperture, the shallower the depth of field. Use a wide aperture to show your in-focus subject against an out-of-focus background. On the other hand, you would use a smaller aperture to get as much of the shot in focus as possible.

It’s worth noting that most lenses lose some sharpness with apertures smaller than f/8 or so.

Shutter Speed

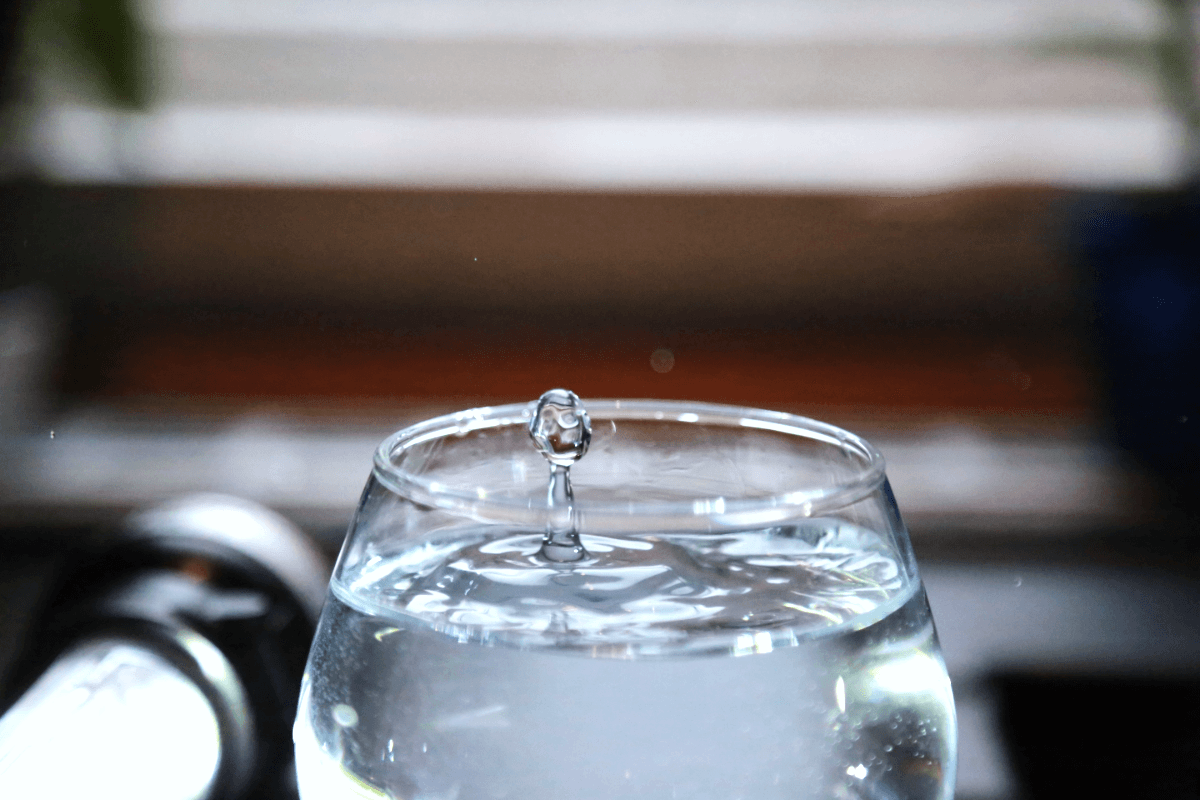

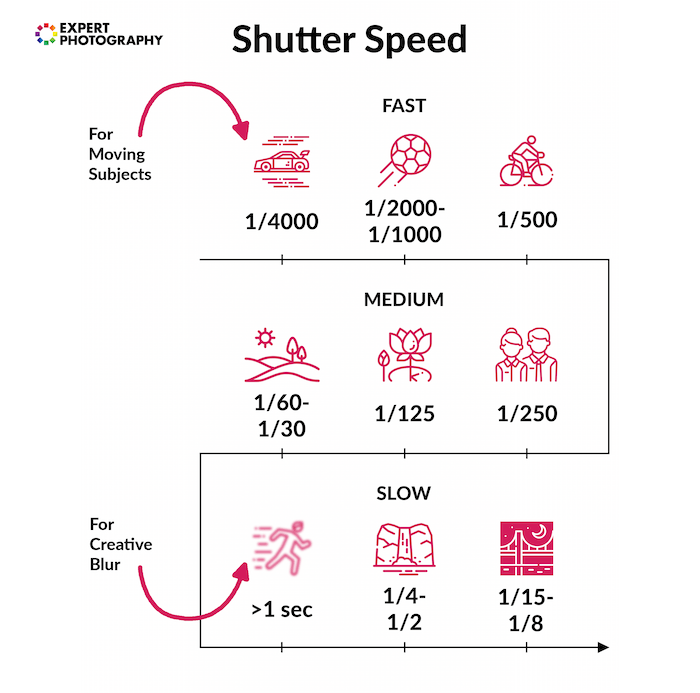

The shutter speed is how long the shutter stays open. This is usually measured in fractions of a second but can go a full second or longer for some shots. The faster the shutter speed, the less light gets to the sensor.

Modern digital cameras sometimes have shutter speeds that boggle the mind. The Sony a1, for instance, has a maximum shutter speed of 1/200,000 s. That’s fast enough to take 100,000 pictures during an average lightning flash!

On most cameras, you’ll usually find a maximum shutter speed of 1/4000 s or even up to 1/8000 s on some high-end cameras. That’s fast enough for some impressive photographs. Using a fast shutter speed is important for two things—preventing blurry photos caused by camera shake and preventing blurry images caused by a moving subject.

Choosing a slower speed allows deliberate blur, which can be an effective way of showing speed and movement within a photo.

With cameras and lenses that have no image stabilization, a rough guide to avoid camera shake is this: choose a shutter speed number that is at least the focal length of the lens. So, for a 50mm lens, you need 1/50 s or faster. With a 200mm lens, you need 1/125 s or faster.

ISO

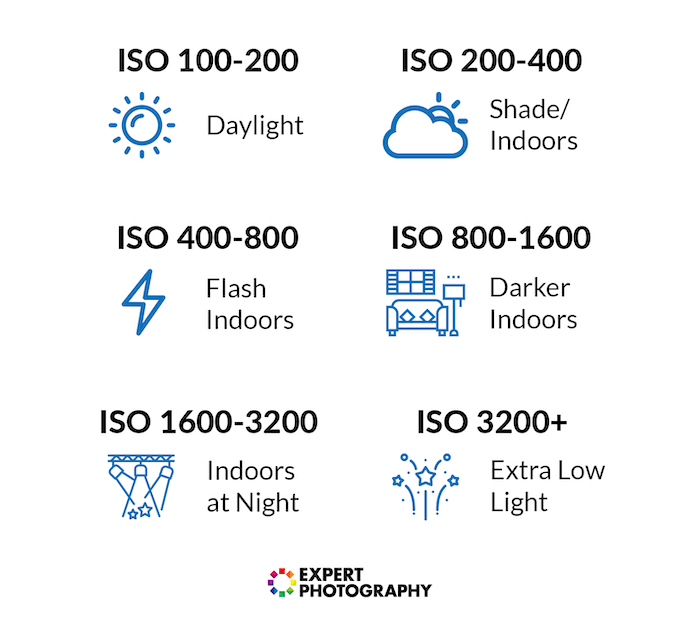

In the days of film, the ASA/DIN of the film told you how “fast” it was. In other words, it tells you how sensitive it is to light. The ISO number has replaced the ASA/DIN numbers, although ISO numbers are identical in their value to ASA. And they still determine how sensitive the film is to light. Or more usually, how sensitive the digital sensor is to light.

If you came to modern digital cameras from the world of film, you’d be amazed at how “fast” sensors are. A fast ISO film would be 400, maybe “pushed” to 800 or even 1600 for very dark settings. But you’d pay the price with lots of grain in your image.

Don’t forget that you had to keep the ISO setting for the whole roll of film. Now, we can change ISO shot by shot. With modern digital cameras, ISO settings of 12,800 are completely normal. And their sensors often manage to keep the noise at acceptable levels. And when they don’t, editing software can take care of it.

How to Set Aperture

A narrow aperture, such as f/16, will keep almost everything in focus because it has a large depth of field.

It’s most useful for landscape photographers, who might use a narrow aperture to show as much detail as possible in the foreground and background. But there’s always a limit to sharpness.

With f-numbers higher than f/22, you start to get diffraction effects. When that happens, the finer details won’t be sharp anymore.

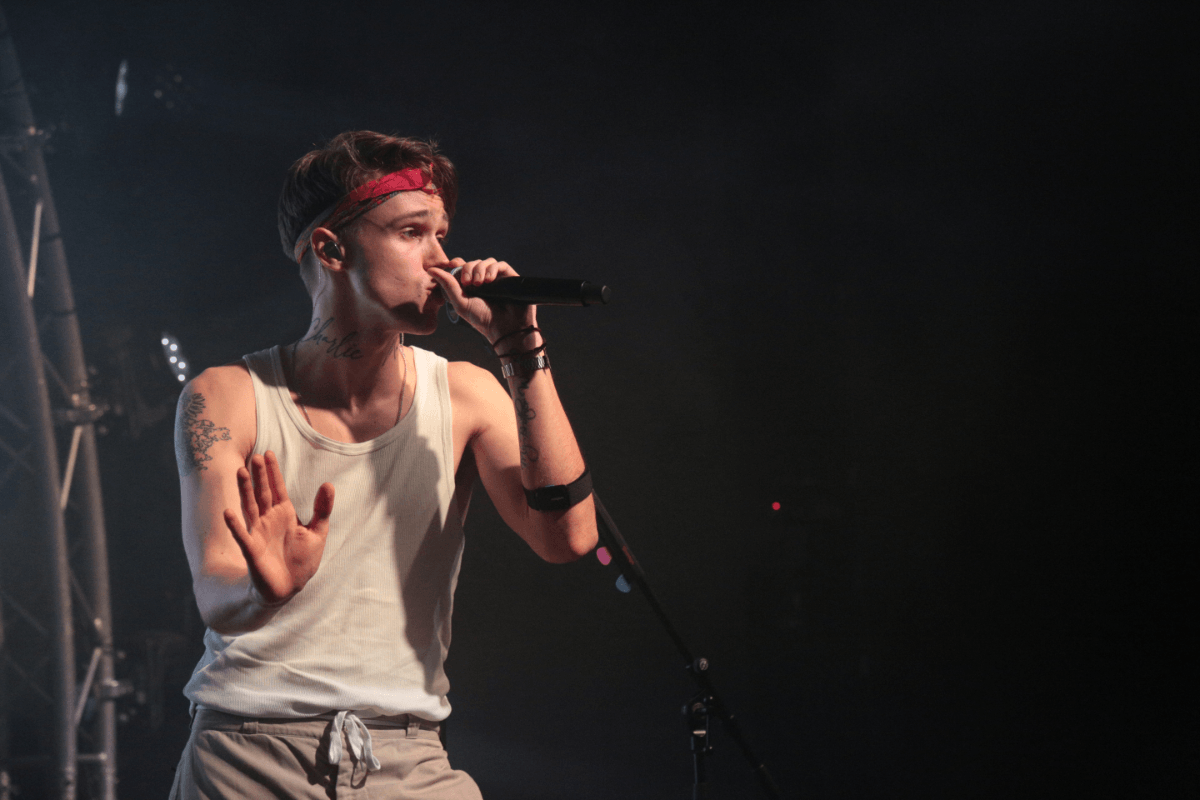

Shooting a photo with wider apertures, such as f/1.8, will have a shallow depth of field. This means only part of the scene is in focus. Portrait photographers tend to use a wide aperture to keep their subject in focus while the background is out of focus.

How to Set Shutter Speed

A faster shutter speed means you’ll need a higher ISO to get the correct exposure. But you get a sharper image because a moving subject is “frozen.”

A slower shutter speed means you can use a lower ISO, but you’ll get more motion blur. Neither approach is right or wrong. It’s just a matter of personal taste.

How to Set ISO

The lower the ISO number, the better the image quality is in smoothness, contrast, and color rendition. In general, it’s a good idea to keep it as low as possible.

But there’s a trade-off. If you’re working in low light, you need the extra brightness from a higher ISO. You have to balance brightness with image quality.

You start to see significant noise beyond 6400 ISO as a general rule. So that’s when you might want to use a wider aperture or longer shutter speed. But it depends on your camera. Modern, full-frame cameras perform much better at high ISOs than older models.

Most cameras will offer you the option of Auto ISO. This means that while you concentrate on getting the exact shutter speed and aperture you want, the camera adjusts the ISO so the exposure is right.

How to Shoot in Full Manual Mode

The best way to get full control over your exposure is to use Manual mode. Assess the scene, and use your judgment to select the appropriate ISO. Once you’ve done that, it’s simply a case of choosing the aperture and shutter speed you need for your photos.

And as we’ve seen, the type of photo you want will determine your choices. For example, if you’re shooting sports or fast-moving wildlife, you probably want a fast shutter speed. But if you’re shooting a still-life with a tripod, you can use slower shutter speeds since motion blur isn’t an issue.

Choosing the right aperture depends on how much light there is and how much of the scene you want in focus. In low-light conditions, a wider aperture tends to be best because it lets more light in. But then you’ll have a shallow depth of field. If you want a deep depth of field, use a wider aperture and adjust your ISO and shutter speed to compensate for the correct exposure.

Conclusion: How to Shoot in Manual Mode

I have recently rediscovered my old files of negatives. And I have been struck by how difficult it was to learn the effects of different exposure settings. There was always a gap between shooting and seeing the result. And there was always a cost involved with experimentation.

There has never been a better time to experiment and learn! Make a mistake, and you can both see it and correct it immediately. Switch that camera dial to “M,” make as many mistakes as you like, and learn the creative freedom that comes from Manual mode!